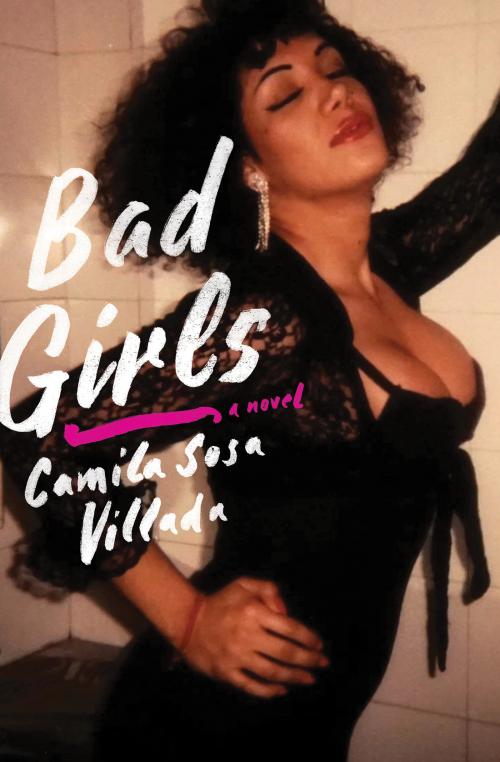

30. Wild Card: Bad Girls by Camila Sosa Villada

List Progress: 16/30

The lives of queer people are far too often filled with both beauty and pain. In Latin America, the travesti community (AMAB people with female gender identities) is often subjected to abuse from the police and their neighbors alike, but they can find community and solace with one another. Bad Girls (Las malas in the original Spanish), is a semi-autobiographical novel by Argentine author Camila Sosa Villada, telling a magical take on her younger days as a sex worker in Córdoba. Poverty, abuse and addiction are kept somewhat at bay by friendship, love and freedom among her peers, but the pain is still there. And the way they intertwine makes for a beautiful novel.

One of the most fascinating things about Bad Girls is how it smoothly weaves magical realism into an otherwise very grounded story. Auntie Encarna is a matriarch travesti who runs a sort of boarding house/commune for the other travestis. She is also 178 years old and her lover has no head, after being decapitated before he emigrated to the city. Maria the Mute is a normal sex worker in the park, navigating the same struggles as the rest of them, until she starts turning into a bird. This is magic without wonder, everyday magic, while the actual awe-inspiring things are holiday dinners around a crowded table and vigils by the hospital bed of a sister dying of AIDS. The narrator Camila is the main character, but only part of the story is about her, with more page space dedicated to chronicling the world she lives in and the people she loves. The great family is rocked when Auntie Encarna finds an abandoned newborn in the park and decides to raise him as her own. But this choice made out of deep love brings further scrutiny to their already scrutinized lives, as small minds hate seeing children and queer people cross paths.

Bad Girls is not for the faint of heart; it is very matter-of-fact about the realities of prostitution, from the dangers to the thrills and joys to the humdrum nights just trying to get by. The reader feels the losses as people leave Camila’s life, through death or distance, and it’s a powerful ache. But the joys and loves that lead to those aches are beautiful while they last, and chronicling them is important. Late in the book, city officials install street lamps in the park where the travestis solicit clients, and the women are forced to work on their streets or out of their homes, in smaller, more dangerous groups or completely alone. Those glaring lights are an imposition and a threat, while the narrative light that this book shines on its characters is warm and soft. And nearly every queer person in this world deserves more warmth than they get.

Would I Recommend It: Very much so.

[…] Biggest Surprise: Bad Girls by Camila Sosa Villada […]

LikeLike